In italiano su Artribune

The starting point of this multi-voice conversation are the student protests that, after months of mobilization in solidarity with Palestine, starting from the campus of Columbia University, in recent weeks have camped on the lawns of over 100 universities in the United States, but also Canada, Australia, and Europe, asking governments to stop military aid to Israel and universities themselves to stop collaboration programs with Israel, particularly in the field of military research.

On the evening of April 31, at the request of President Nemat Shafik, the New York police raided the Columbia campus, clearing the camp and the occupied building, and arresting dozens of students. Clashes, evictions and arrests are underway in other universities. Yet, in this historical moment marked by the darkness of a genocide committed live on social media, and by a massive return to investment in weapons, these protests turn on a light of hope.

As in 1968, when Columbia was one of the hubs of the protest against the war in Vietnam, the encampments tell us of a generation capable of mobilizing against a war that is massacring a civilian population, razing houses, hospitals, schools, universities, up to that nothing remains standing that may even remotely resemble a shelter, nor an area (or a life) free from rubble. The encampments also speak to a solidarity towards the Palestinian cause, that is, towards what, from many points of view, appears to be a war of liberation against a form of occupation. The occupation of a land that could have become a free, multilingual and multi religious state and which, instead, someone decided to segregate, divide, and empty of its inhabitants.

In this sense, the precariousness and fragility of the university camps echoes not only the current situation of the Gaza population (on whose tents “thank-you” writings for the American students have appeared), but the decades-long history of millions of Palestinian citizens, in 1948 suddenly expelled from their homes and villages. Houses and villages then razed to the ground to erase every trace and memory of their existence, or immediately reassigned to the citizens of the new State of Israel.

It is not against the people of Israel, but against the violence of that founding act of a state imposed on a territory and a population that did not have a possibility of choice, and then, again, against the continuous expansion of that state through the construction of colonies, and against the practices of extreme spatial and racial segregation carried out by its governments that students protest.

This was the meaning of the pro-Palestinian solidarity document written shortly after the terrible events of October 7, to remind that those events could not be seen outside the historical context in which they occurred. That horrible violence, in fact, did not come from nowhere but was part of a trail of blood that, as of October 7, 2023, had already seen, in 2023, 250 Palestinians die, including 47 children, killed by Israeli soldiers. It is in this sense that we must read the defense of that document by a long list of Columbia professors who recalled that there was nothing anti-Semitic in the students’ statement but rather a legitimate political, legal and, I want to add, historical debate.

To build on this framework, I decided to ask some protagonists of architectural theory and practice, variously involved in architectural education at Columbia, how their teachings intersect with the war in Palestine and the ongoing protests. My first interlocutor is Paulo Tavares, architect, educator, and, together with Gabriela de Matos, winner of the Golden Lion at the last Venice Biennale with the curatorship of the Brazilian pavilion called “Terra/Earth.”

Paulo, my general question therefore is about the intersection between your current seminar at Columbia titled “Reparation Architecture,” and the students’ protests. I see a deep correlation between the postcolonial critical framework of your work and the current protests, and I am asking you to elaborate on this because this link, that for those of us working within this critical framework is so evident, is clearly not visible to those who accuse the protests of anti-Semitism.

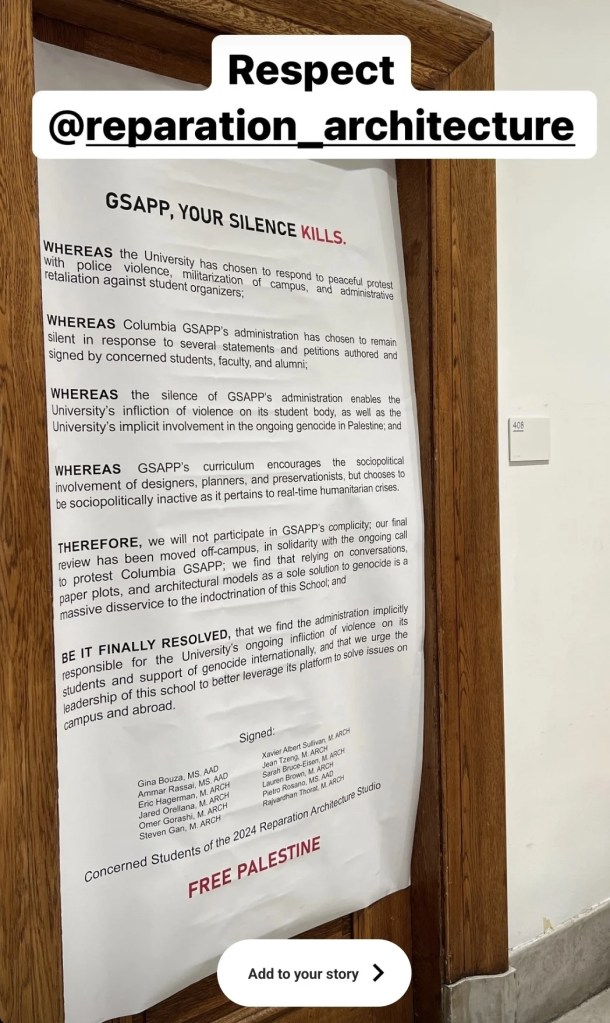

PT: First it is important to say that the students’ protests and, more specifically, the Gaza Solidarity Encampment that was set at Columbia University and sparked the various encampments around US and beyond, is fundamentally a student initiative, a movement organized and maintained by the youth. I say this not because I want to distance the studio Reparation Architecture from the protests, to the contrary. After the police action against protesters we released a statement in support of the encampment. But because it is important to acknowledge that, as many times in history before, it is the young generation that is setting the moral compass of political action and resistance to this unlawful, shameful genocidal war on Gaza. That said, the ways in which the encampment embody a claim for decolonization and liberation is in various ways related to the spatial contexts and issues we address under the framework of Reparation Architecture, not least because the colonial occupation of Palestine and the apartheid regime imposed by the State of Israel on Palestinians is an important context for the study of how spatial elements and infrastructures operate as colonial tools and instruments of oppression, as many scholars have debated in recent years. Many of the territories and situations addressed by students through their projects touch upon questions of memory, displacement, colonization and spatial exclusion that we see acutely expressed in the Palestinian territories under occupation. So naturally the students’ protest had a significant impact in our studio at GSAPP, because our group was very aware of how injustices play out in space, and it came as a shock to witness the disproportionate use of police forces on campus to repress their colleagues. To that end they organized a protest during the final reviews at GSAPP, placing a large poster in the school that called faculty and directorship to break the silence on the genocide in Gaza.

MLP: I also want to ask you—to further unpack the critical framework of your work—since you define your practice as something that dwells on the border between architecture and advocacy, defense for who, and why?

PT: The principle is that, if we understand the city as a right, that space, land, environment are rights, then we must conceive architecture and spatial practices as forms of advocacy of such rights. In our practice we work mainly with communities under state or corporate violence, who are undergoing severe rights violations or struggling to access recognized rights. Rights are not the only, and at many times not the most effective, venue to pursue social-spatial and environmental justice. For example, we have seen, time and again, how principles such as human rights or humanitarian law can be turned upside down and operate as rhetoric and legal dispositives to allow military interventions and even grant legitimacy to barbaric state violence, as in the case of the current war on Gaza. Gaza exposes not only the flaws of the liberal discourse by Western powers and the Western media, but also how the international system of justice is ineffective, not to say completely biased in favor of Western powers. Yet rights can also be mobilized as powerful, important instruments in the struggle for justice. Once again Gaza sets an example: human rights activists could foresee that South Africa’s application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide against Israel in the ICJ would most probably lead into no significant action. Nonetheless, it served as a strong gesture reframing the narrative on the war that dominated the international news and political discourses, not only of the Israeli leadership, but also of Western leaders such as in the United States and Germany.